Hopeful Witness in an Age of Pessimism

John Coffey, Professor of History

“The views and opinions expressed below are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the Jubilee Centre or its trustees.”

We live in pessimistic times. In the West, at least, the giddy optimism that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall has long since evaporated. Doomscrolling has become a daily ritual. We find much to worry about: economic insecurity, growing inequality, geopolitical conflict, climate change, the impact of AI, plunging birth rates. Pundits and politicians declare that ‘broken Britain’ is in steep decline. It no longer seems obvious that ‘the arc of history bends towards justice’. Even Christians, despite their faith in providence, find themselves alarmed and depressed in the face of an uncertain future.

At times like these, we need historical perspective. For we are hardly the first generation to face troubled prospects. Indeed, many of our ancestors confronted dark times and daunting challenges with courage and conviction. In his recent Reith Lectures, the Dutch historian Rutger Bregman notes that the past is ‘a graveyard of disasters’ but also ‘a reservoir of hope’. Against the fatalism and cynicism of our own day, he appeals to the early abolitionists, ‘a small band of renegades’ who sparked a ‘moral revolution’. As Bregman observes, they were attempting something unprecedented – they launched what many see as the most influential human rights campaign of the modern age.

The leading abolitionists, especially Thomas Clarkson and William Wilberforce, are the protagonists at the centre of Bregman’s second lecture, ‘How to Start a Moral Revolution’. Much studied, and much debated, they are just two figures in a remarkable tradition of Christian social reformers in modern Britain, one that stretches from William Tyndale and John Lilburne to John Howard, Elizabeth Fry, Lord Shaftesbury, Charles Kingsley, Joseph Rowntree, Josephine Butler, William Booth, and William Temple. Within that tradition there is an important but neglected strand of Black Christian activism. Its leading voices do not feature in the older literature on Christian social reformers, but they are now being rediscovered. They offer us a remarkable example of hopeful witness.

The Prophetic Witness of Britain’s Earliest Black Writers

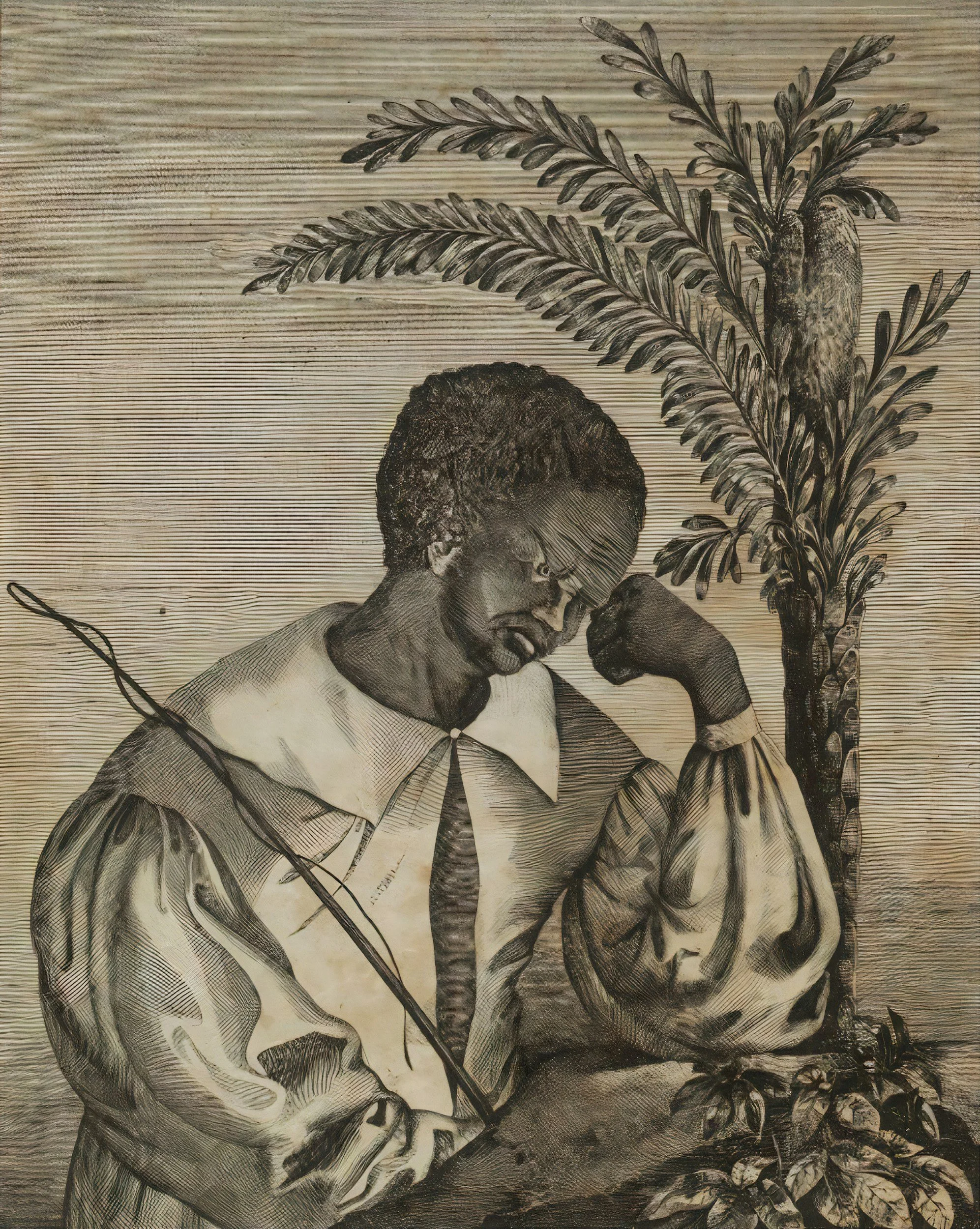

The long history of Black Christian activism in Britain stretches back to the 1780s but it is little known. Excavating that history has been the work of secular scholars rather than church historians. And it is in schools rather than churches that children are likely to learn about Olaudah Equiano or about Frederick Douglass’s tour of Britain. The resilience and resourcefulness of these figures is extraordinary. Most had been enslaved, and some were survivors of the Atlantic slave ships. They faced a world that was often profoundly hostile to their presence. Yet through faith and Christian community, they found a voice and began to testify.

It’s a striking fact that many of the earliest Black writers in English were evangelicals, often connected to the Calvinistic Methodism of the Countess of Huntingdon. Briton Hammon’s captivity narrative, published in 1760, has been memorialised as the first published African American (and Afro-British) prose text. James Gronniosaw’s 1772 autobiography initiated the tradition of the Anglo-American slave narrative. Phillis Wheatley’s 1773 volume of poetry made her the first published woman of African descent, and only the second American woman to publish a book of poems. Ottobah Cugoano’s Thoughts and Sentiments was the first antislavery tract published by a former slave. Olaudah Equiano’s 1789 autobiography, The Interesting Narrative, made him the first black Atlantic author to make a living from his royalties. These early Black evangelicals, many impacted by the ministry of George Whitefield, were steeped in the Bible – the title pages of their books often bear biblical mottos. Their memoirs are conversion narratives as well as slave narratives.

Long neglected, these figures are now the subject of a burgeoning literature written by literary scholars, historians, and even philosophers, and their achievements are increasingly recognised. Cugoano and Equiano, for example, formed an organisation called ‘The Sons of Africa’, and wrote joint letters to the newspapers about the plight of the Black poor in London as well as against the Atlantic slave trade. They collaborated with well-known social reformers like Granville Sharp, who promoted a new settlement in west Africa, Sierra Leone. That was populated by Black refugees from the United States, led by pastors like the Baptist David George and the Wesleyan Boston King. Meanwhile, Equiano joined the London Corresponding Society, a radical political movement campaigning for popular democracy, a group led by the devout Scottish Calvinist Thomas Hardy.

Equiano and his friends wrote as prophets, bearing witness against the bad faith of Christian Britain. After describing the horrors of the Atlantic slave trade, Equiano asks: ‘O, ye nominal Christians! might not an African ask you, learned you this from your God? who says unto you, Do unto all men as you would men should do unto you?’ Equiano highlighted the gulf between Christian pride and Christian performance. British Protestants preened themselves on their religious identity, their liberty, and their happiness, but on the coast of west Africa and the plantations of the Caribbean, the British were notorious for their cruelty.

In their books and in letters to newspapers, the Sons of Africa quoted the Bible, challenging Britons to live up to their own Scriptures. Alongside the Golden Rule, they cited the law of Moses: foreigners should be protected by the same law as Hebrews (Numbers 15:15-16). Equiano liked to quote the words of Job: ‘Was not my soul grieved for the poor’ (Job 30:25). In letter after letter, he and his friends reminded Britons that ‘Righteousness exalteth a nation, but sin is a reproach to any people’ (Proverbs 14:34). To establish the equality of Africans and Europeans, they cited the declaration of the Apostle Paul: ‘God hath made of one blood all nations of men’ (Acts 17:26). Equiano ended his Interesting Narrative with the observation that the point of life was to learn ‘to do justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly before God’ (Micah 6:8).

Writing out of the experience of slavery, these Black reformers recognised the radicalism of biblical social ethics. Equiano boldly argued that racial ‘intermarriage’ – something frowned upon by many – was perfectly biblical. Had not Moses been married a Cushite wife (Numbers 12:1)? Equiano himself crossed racial lines by marrying an Englishwoman from Ely, Susannah Cullen. Cugoano called for ‘a total abolition, and an universal emancipation of slaves, and the enfranchisement of all the Black people’ in the Caribbean, ‘without any hesitation, or delay for a moment’. Wherever ‘the true religion is embraced’, he argued, ‘the blessings of liberty should be extended’.

Frederick Douglass and Black Abolitionists in Victorian Britain

That same Black voice – radical and biblical – was heard again in the mid-nineteenth century, when formerly enslaved persons from the United States visited the British Isles on speaking tours. The most famous was Frederick Douglass, the fugitive slave who fled to Britain in 1845. Like Equiano, Douglass toured England, Scotland, and Ireland, selling his book and giving electrifying speeches before great crowds in Britain’s largest civic halls and churches.

Douglass had immersed himself in the Bible during his days as a slave in Baltimore where he joined a Methodist small group. His autobiographical Narrative (1845) ended with a powerful indictment of proslavery religion: ‘I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land.’ This was a message that went down well in 1840s Britain, which had abolished West Indian slavery in the 1830s. British audiences were quick to boo and hiss when Douglass laid into America’s proslavery preachers, and they cheered when he praised British abolitionists.

Yet Douglass had an uncomfortable challenge for British Christians. Too many, he argued, prioritised networking with American Christians over prophetic witness. The chief culprits here were the Free Church of Scotland, newly established in 1843 and desperate for funds having left the Church of Scotland. They had turned to Southern Presbyterians, and raised funds from pastors and churches who were unapologetic in their defence of racial slavery. Douglass was appalled by their complicity. He led a nationwide campaign in Scotland to ‘Send Back the Money’. Although he had much public support, the money was not returned, and it was only in 2024 that the Free Church ‘acknowledge[d] with sorrow the actions of our forebears’.

Douglass’s other campaign was even higher profile, because it concerned the inter-denominational Evangelical Alliance. Inaugurated at an 1846 convention of 900 evangelicals, the Alliance aimed to create a new Protestant international that would unite the evangelical churches on both sides of the Atlantic. The issue of slavery, however, proved a major sticking point. The question was simple: could slaveholders and apologists of slavery be admitted as members of the trans-Atlantic Alliance? In the ‘yes’ camp were those who saw the Alliance as being based solely around evangelical Protestant doctrine. In the ‘no’ camp were those who saw American racial slavery as a glaring case of grave and unrepentant sin. Douglass, as a survivor of enslavement and one of the most eloquent orators of the age, was especially effective in arguing for no compromise. Douglass made a second visit to Britain in 1859-60, on the eve of the American Civil War, and Black abolitionists strengthened the lobby against a British alliance with the Confederate South.

Black abolitionists often spoke in churches, and a number of the Black speakers who toured Britain were pastors. Samuel Ringhold Ward had been a newspaper editor and the pastor of white congregations in America; in Britain he shared platforms with Lord Shaftesbury and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Alexander Crummel, an ordained Episcopalian, studied at Queens’ College, Cambridge, before ministering in Liberia. James Pennington was a Presbyterian pastor who published his autobiography in London and received an honorary doctorate from the University of Heidelberg. Another Presbyterian pastor, Henry Highland Garnet, denounced slavery as ‘directly antagonistic to a pure and holy religion’. After the Civil War, the female Black evangelist Amanda Smith also toured Britain, even addressing the Keswick Convention.

Such figures, with their testimony against slavery and racial segregation, shaped the ethos of British Christians. They were known to white reformers such as Granville Sharp and Lord Shaftesbury. Their books were read by hundreds of thousands, and their speeches heard by tens of thousands in cities and towns the length and breadth of Britain. Southern proslavery clergy, by contrast, were wary of visiting the United Kingdom. Thus British Christians were largely insulated from the most egregious forms of proslavery propaganda, and exposed to the prophetic voice of Black Christians.

Dr Harold Moody and Twentieth-Century Social Reform

The influence of Black reformers persisted in the first half of the twentieth century. Dr Harold Moody was one of the most important Black leaders in Britain from the 1920s to the 1940s. Born in Jamaica, Moody trained as a medical doctor in London, and became the founder of the League of Coloured Peoples in 1931, an organisation which counted Jomo Kenyatta, Paul Robeson, and C.L.R. James among its members. He campaigned for racial equality in the armed forces and his son became a colonel in the British army.

As Prof. David Killingray documents, Moody was a devout Christian and a lay preacher for whom prayer and social reform belonged together. He was active in the Congregational Union, chair of a missionary society, and president of the Christian Endeavour Union. Like Equiano, he saw the ‘colour bar’ as a violation of biblical teaching on the unity of the human race. Also like Equiano, he has been listed among ‘100 Great Black Britons’ and celebrated in a Google Doodle.

Hopeful Witness in the Twenty-First Century

Equiano, Douglass, and even Moody did not start out with the social capital of a Wilberforce or a Shaftesbury. Indeed, many Black Christians had been trafficked and enslaved. They had every reason to despair. Yet through faith, they found community and hope. And they found a voice to speak up and bear witness in dark times.

Most of us have enjoyed far easier lives. Yet affluence can go hand in hand with apathy. Faced with the mounting problems of the twenty-first century, it is tempting to lapse into fatalism. But Christians believe in resurrection, and we are surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses. There is a mighty tradition of Christian social reform. As we confront the challenges of the twenty-first challenges, we should return to it as a source of hope.